I recommend reading this blog post if you are a microbiologist interested in (1) isolating more diverse organisms, (2) characterizing metagenomes in more detail, or (3) understanding why genomes are the way they are. This blog post will help you build on my preprint with Cultivarium, “Predicting microbial growth conditions from amino acid composition“, which provides a tool called GenomeSPOT. I recommend reading the preprint, especially to understand the limitations of the tool.

- Understanding the models

- Four suggestions for better isolations inspired by this work

- Using this tool for metagenomics

- Bread crumbs for genomics

- Wrap-up

Background:

- What’s Cultivarium? It’s a focused research organization from Schmidt Futures that’s producing tools and data to accelerate microbiology research. Check out resources for genetics (here and here and here) and stay tuned (cultivarium.org and @CultivariumFRO).

- What’s the preprint? You want to know the conditions a microbe needs to grow. Previous research has provided models to predict optimum temperature for growth from amino acid composition and described correlations between optimum salinity and amino acid composition. We extend that work to provide models for not only temperature but also salinity, pH, and oxygen.

- Why does that matter? We can now describe microorganisms in nature in terms of their physical and chemical niche. We can use this to learn find our if we’ve been doing anything wrong in cultivation. We can further explore why these and other conditions influence microbial growth through the cost of protein biosynthesis.

Understanding the models

A brief explanation of models

We wanted to predict a variable like optimum growth temperature, which we’ll call the “target.” We had available a variety of data measured from a genome, which we’ll call “features.” We took a model, like a linear regression, and “fit” it to the training data. What the means is that the model found the way to weights and combinations the features in order to optimally predict the target. Different models have different ways of weighing and combining features and different ways of “scoring” the best fit. As you can imagine, the features with the strongest weights are often those most correlated to the target variable.

The risk with modeling is that the model doesn’t apply to new examples. The weights and combinations that provide a good prediction of the target for one set of genomes may not work for another set of genomes. That’s may seem counterintuitive, but remember that spurious correlations happen all the time and are more likely the more variables (features) you measure and the fewer examples (genomes) you use. Therefore, when we were choosing which models to use, we compared them by how well they scored on genomes that were held out of model training (“cross-validation”). We also held a “test” set of genomes out that were not used in model training or selection in any way but reserved to check that the model was still predictive on new organisms

In microbiology, spurious correlations can result from the phylogenetic relationships, so we — as everyone should — took steps to account for these biases.

The oxygen / amino acid surprise and why it matters

The biggest finding is that amino acid composition is so influenced by oxygen, so it’s a good place to build an understanding.

Here’s how non-obvious this finding is: I tried to predict oxygen with amino acid composition because I thought it wouldn’t work, and I was worried at first when it did work. My expectation of amino acid composition was that extremes of temperature, pH, salinity could shift some amino acids but that overall composition is influenced by (A) the influence of GC content on codon usage, (B) phylogenetic history, and (C) not much else. Was this model just biased by GC content and phylogeny?

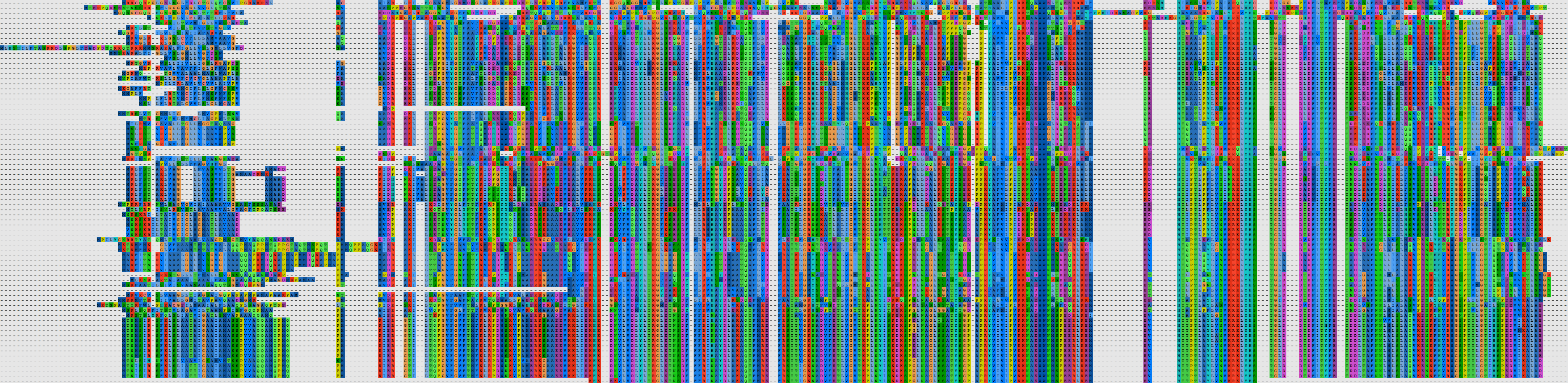

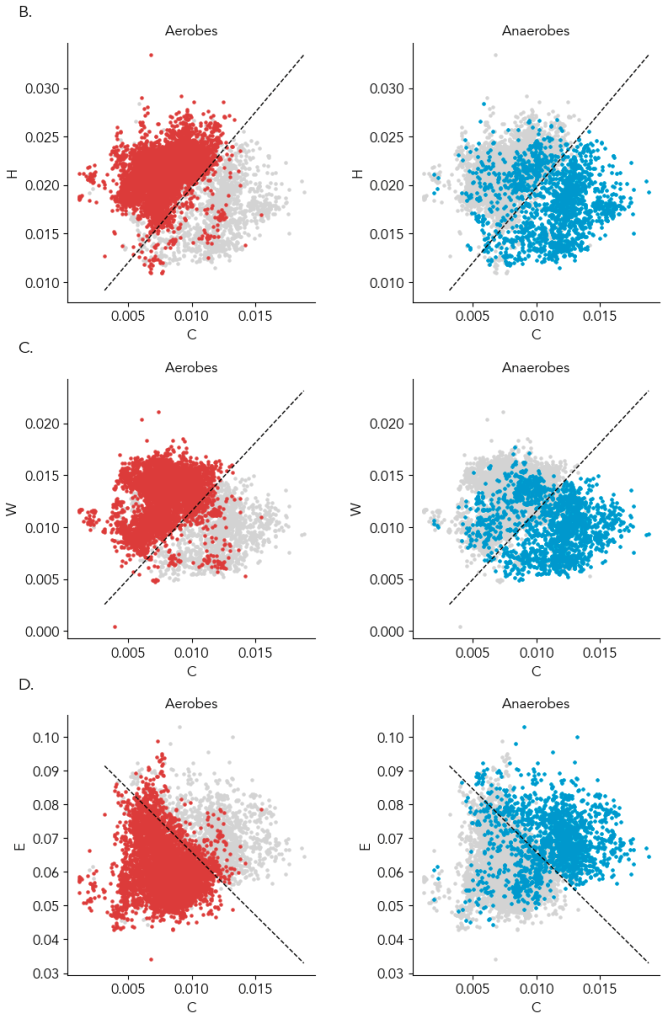

In the preprint, we show amino acids predict oxygen in a GC content and phylogeny independent way. For those skeptical of modeling, the most compelling data is that just two amino acids can provide a ~90% accurate classification of a microbe as aerobic or anaerobic, and you can see the clustering yourself in the below scatter plot (Supplementary Figure 4). Specifically, the average frequency of cysteine with histidine, tryptophan, or glutamate (glutamine is a runner up) in the genome is enough to know if a microbe can live in the presence of oxygen or cannot. In the plot below, a line from a logistic regression uses the amino acid frequencies on the x- and y- axes to classify microbes as aerobes or anaerobes (highlighted in left and right plots). ~95% of aerobes and ~85% of anaerobes fall on either side of the line. That isn’t machine learning magic; it’s real, tangible biology. And interpretable: we can try to understand why some anaerobes are in the aerobe “region”.

We haven’t had good ways to classifying a microbe as an aerobe or obligate anaerobe. Doing it from genes is not as straightforward as you’d think. Even obligate anaerobes have oxygen tolerance genes like catalase or peroxide and genes for using oxygen as a respiratory electron acceptor, so a manual determination is tricky. Gene-based models to provide automated prediction of oxygen tolerance appear good (especially Davin et. al 2023), but there’s always a nagging worry about how well they work for new groups of life or for incomplete genomes. I expect the new model to be very helpful because it’s grounded in biological first principles.

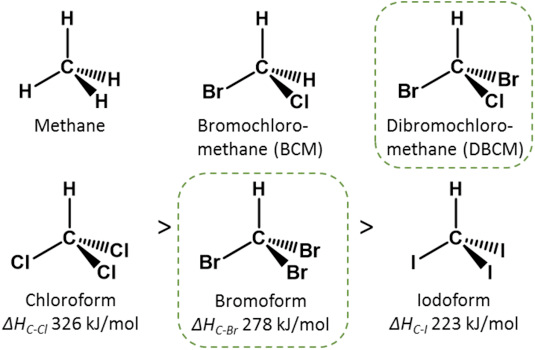

Specifically, we hypothesize oxygen influences amino acid content for bioenergetic reasons:

- Sulfur assimilation take a lot more energy when you have to reduce sulfate (oxic habitats) than when there’s a lot of reduced sulfide around (anoxic habitats). Also, oxidation of cysteine to cystine causes some important problems for microorganisms. Solution: to become an aerobe use less cysteine. (Full credit to Paul Carini for this insight).

- Respiring oxygen provides a lot of energy, making energy-intensive amino acids relatively less costly. Solution: if you’ve become an aerobe, it’s OK to use more histidine and tryptophan over less costly similar amino acids.

A critical decision was to lump everything but obligate and unspecified “anaerobes” into aerobes: aerotolerant anerobes, microaerophiles, facultative aerobes, facultative anaerobes, simply “aerobes,” and obligate aerobes. Researchers have been close to finding the patterns we described for decades (Naya et. al 2002, Vieira-Silva & Rocha 2008) and even recently (Davin et. al 2023, Flamholz et. al 2024), but how to classify facultative anaerobes complicated their analyses. We decided to lump them together because compared to obligate anaerobes both aerobes and facultative anaerobes have similar numbers of oxygen-utilizing enzymes (Jablonska & Tawfik 2019). We found that in terms of amino acid composition, too, facultative anaerobes are essentially aerobes.

I recommend the following decision tree to classify microorganisms by oxygen use:

- GenomeSPOT predicts not oxygen tolerant: Obligate anaerobe

- GenomeSPOT predicts oxygen tolerant:

- Has genes to respire oxygen: Aerobe

- Has genes to respire other electron acceptors or to perform fermentation: Facultative anaerobe / facultative aerobe

- No other energy sources: Obligate aerobe (in practice hard hard to be confident)

- Does not have genes to respire oxygen: Aerotolerant anaerobe

- Has genes to respire oxygen: Aerobe

Four suggestions for better isolations inspired by this work

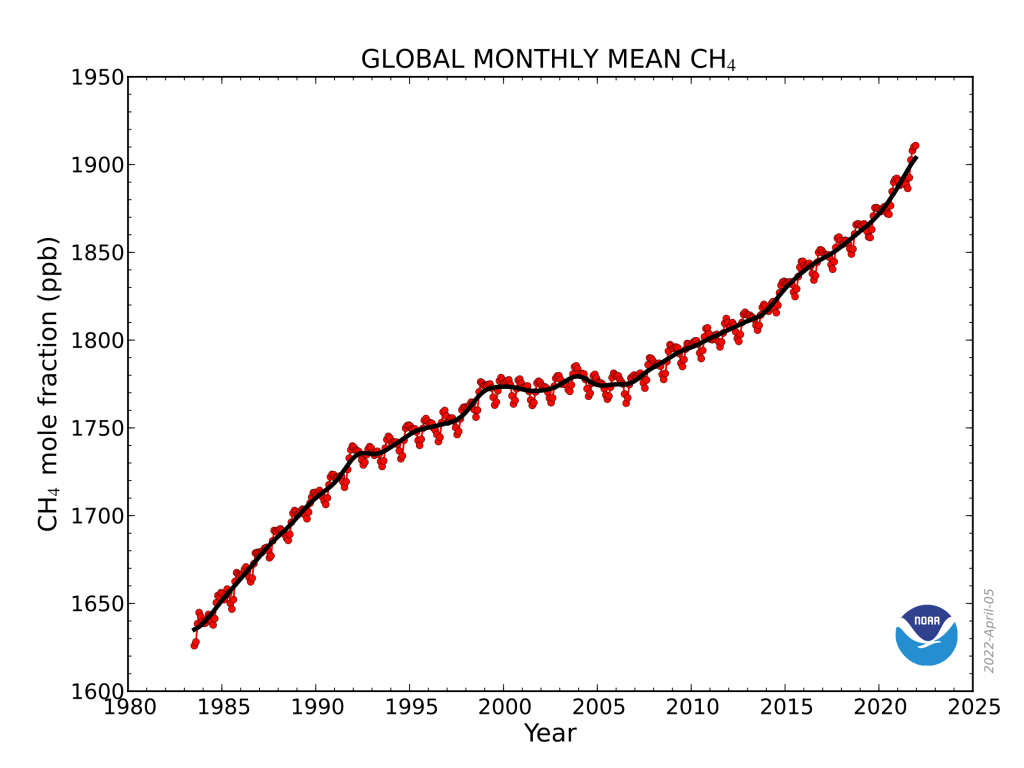

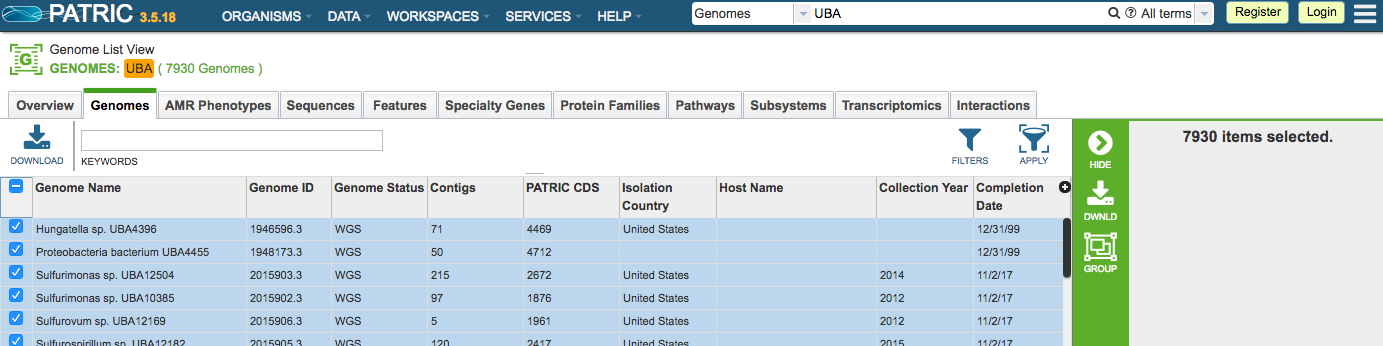

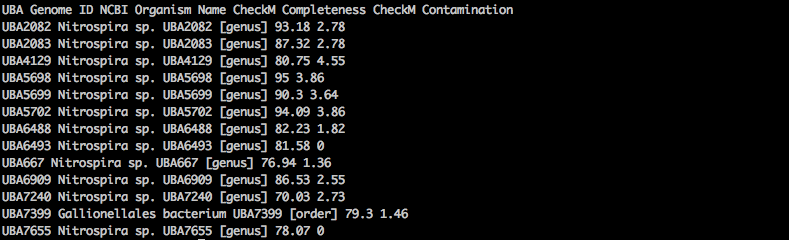

70% of microbial species, classes, etc. are not isolated (source: GTDB). With our tool we could show that are enriched in anaerobic and thermophilic microorganisms. Among the metagenomes researchers have chosen to sample, those organisms are ~50% and ~20% of species and x- and x-fold underrepresented in culture collections. (Note that because most microbial biomass in the subsurface, it’s likely that current sampling underestimates the diversity of anaerobes and thermophiles).

Use anoxic conditions and higher temperatures to isolate more novel organisms

Anoxic conditions are obvious, but why is 37C not good enough to culture moderate thermophiles? After all, they should grow at that temperature.

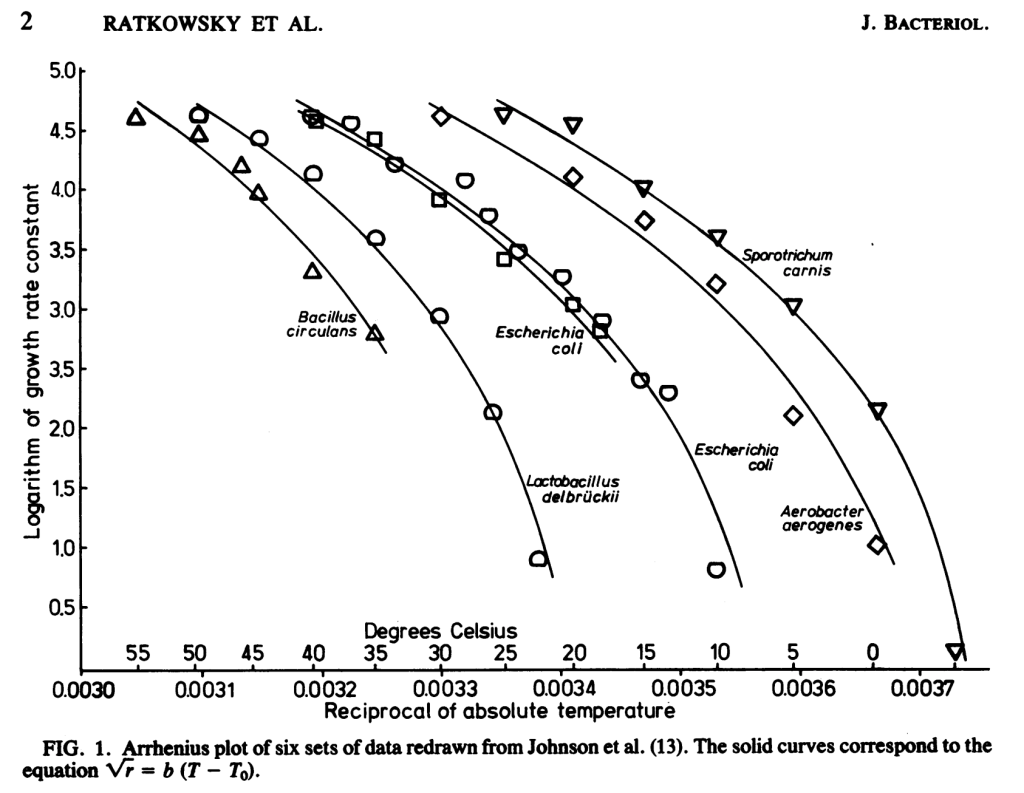

Due to the Arrhenius relationship between temperature and biochemical reactions, at 10C below optimum temperature microbes grow at half the rate . When we already have an isolate, we may be OK with growth conditions that are simply permissive. But during isolation, when microorganisms are competing with one another, this halved growth rate would lead to out-competition by colonies with optimum temperatures equaling the incubation temperature. For example, in the below plot from Ratkowski et. al 1982, at 35C Lactobacillus delbruckii (optimum ~47C) grows at a 1/e the rate (1 natural log less) of Escherichia coli (optimum ~37C), which adds up over the many generations required to produce a colony. Beyond a 10C drop in temperature, the drop in growth rate exceeds the Arrhenius relationship.

Is it the temperature making you sweat or is that 45-60C is a lot harder to work with than 25-37C because of issues like agar gelling and water evaporation? Weigh the costs with the benefits of increased diversity and potential relevance for biotechnology. Getting set up for higher temperatures and sampling slightly higher temperature environments (near subsurface, sun-baked soils and sediments, warm climates, etc.) could be worth the cost.

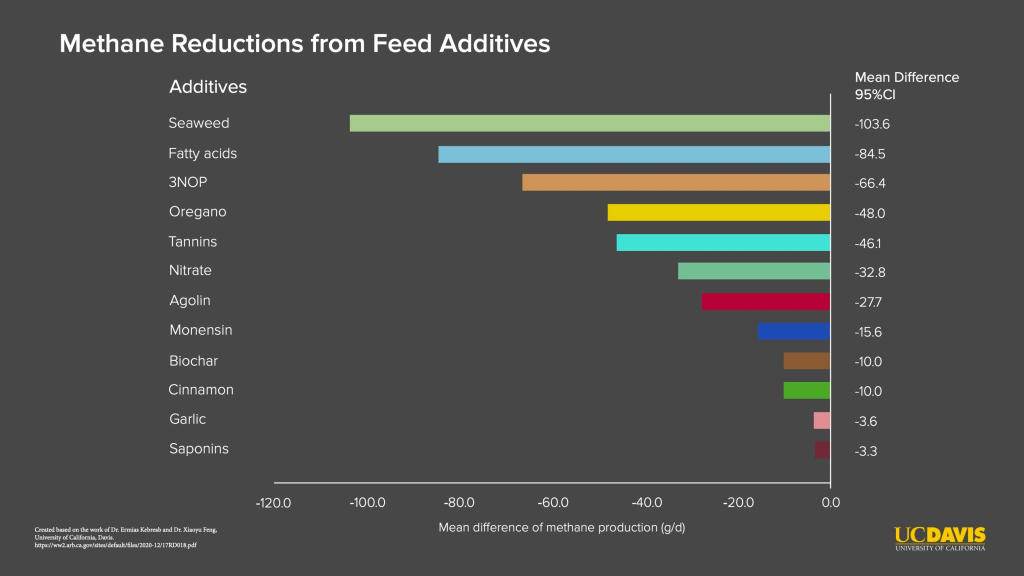

Worry about the oxidation state of media components provided to anaerobes

Seeing the influence of oxygen content on amino acid composition, especially cysteine, makes me imagine that the media we provide anaerobes could be toxic to many anaerobic lineages. Uncultivated anaerobes tend to have higher cysteine content than cultivated anaerobes (data not shown in preprint), hinting that this is indeed the case.

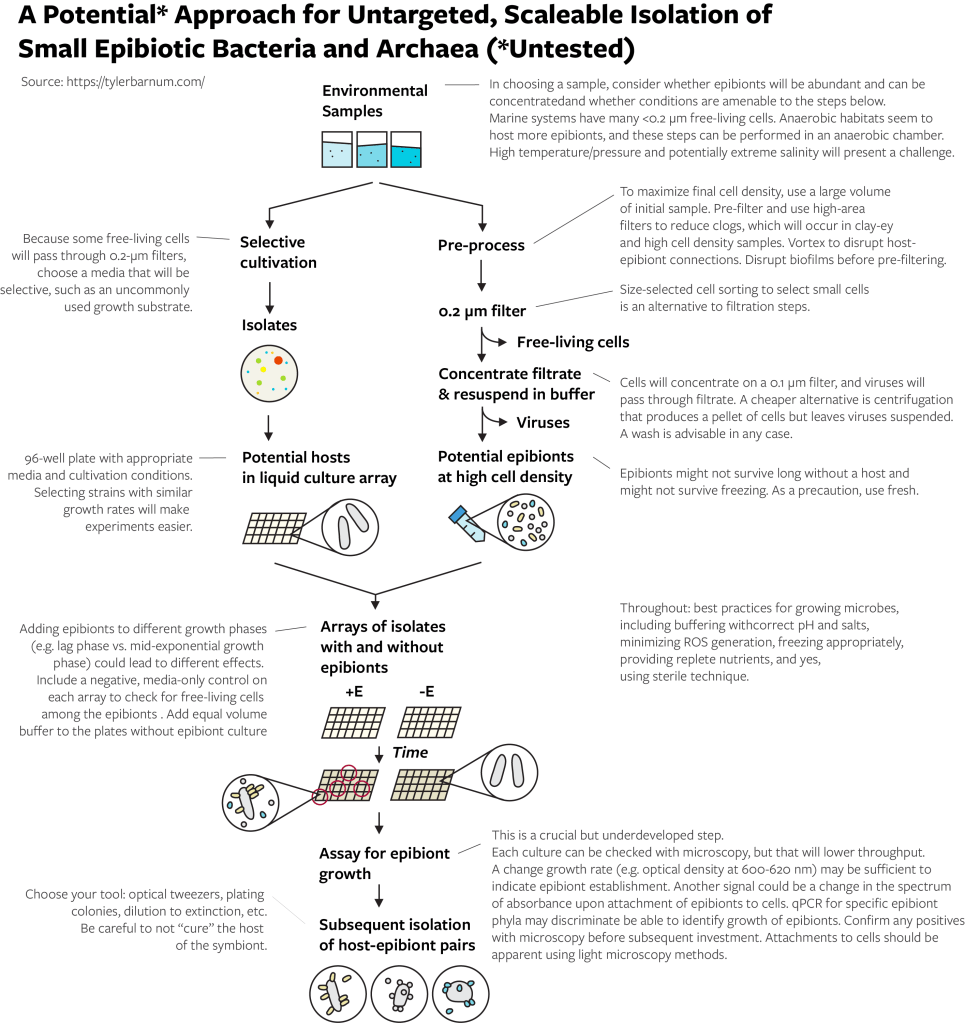

I think I used the same stock of cysteine as a reductant for my entire PhD, and I removed oxygen from medium components like yeast extract by sparging but never chemically reduced them. What if cystine (oxidized cysteine) in those media components inhibited most of the strains in samples before I could isolate them? I usually provided sulfate as a source of sulfur. What if many species require sulfide or cysteine as a source of sulfur instead? What if – here’s what may be new ideas – many anaerobes can’t be isolated because in order to grow well they require a partner organism to detoxify cystine to cysteine or reduce sulfate to sulfide?

Provide different combinations of growth conditions based on metagenomics

Using this tool with metagenomics, you can describe the growth conditions of all microorganisms in a community. Therefore, you can estimate roughly what portion of species will grow at a given pH, salinity, temperature, and oxygen condition. In many cases you will find that using 1 or 2 media is only able to isolate a small minority of the diversity of a community. Try a few more media at different conditions. If you don’t have a metagenome for you sample, refer to the data by habitat from the JGI Genomic Catalogue of Earth’s Microbiomes provided as a supplement.

Don’t use this tool as the sole motivation for targeted isolation

“A tool to provide growth conditions for metagenome-assembled genomes will help me target a specific organism for isolation!” – someone leaping before they look. Targeted isolation of a single microbe is very laborious and high risk. Many microorganisms will not grow because of other reasons than the right growth conditions haven’t been tried. You can use the tool for targeted isolation, and anyone already doing targeted isolation should use the tool, but you should probably just use this tool to maximize the diversity you can capture from a given habitat, as discussed above.

Using this tool for metagenomics

Metagenomics has provided astounding insights into microbial biology, especially phylogeny, metabolic diversity, and biological interactions of uncultured microorganisms. Working in soil metagenomics at Trace Genomics made me appreciate that the physical and temporal variability of microbial communities, which is at its peak in soil. In many microbial environments, what looks like a homogenous environment to us is very heterogeneous on the micro-scale. GenomeSPOT is therefore useful in two ways:

- This tool allows us to describe individual microorganisms in terms of physical and chemical niche. What can learn about ecology now that can estimate these traits?

- This tool allows us to represent communities in terms of distributions of physical and chemical niches. Kurokawa et. al 2023 showed how an essentially identical prediction of optimum growth temperature can serve as a “thermometer” for the temperature experienced in microbial communities. Now you can also try** that for salinity, pH, and oxygen. (** we didn’t test the average predicted condition for a community to real measurements, so this remains to be proven). We really didn’t explore this too much, leaving the fun analyses to the reader.

Thinking at the microscale may help to explain why we see elevated temperature be more common. Sunlit surfaces can temporarily be much hotter than their surroundings. Perhaps there are lots of hidden thermophiles that grow only when the sun is shining. One indication of this is the high average optimum temperature for microorganisms from the surface of macroalgae (Fig 4A).

Bread crumbs for genomics

Explaining DNA and amino acid composition of genomes

Other factors that influence genome composition include nutrient limitation affecting amino acid usage (Grzymski & Dussaq 2012), and mutations in DNA due to environmental factors (Ruis et. al 2023, Aslam et. al 2019, Weissman et. al 2019). The finding that growth conditions, especially oxygen, influence amino acid composition makes it tantalizing to try to create a causal model of how a microorganism’s niche influences its genome.

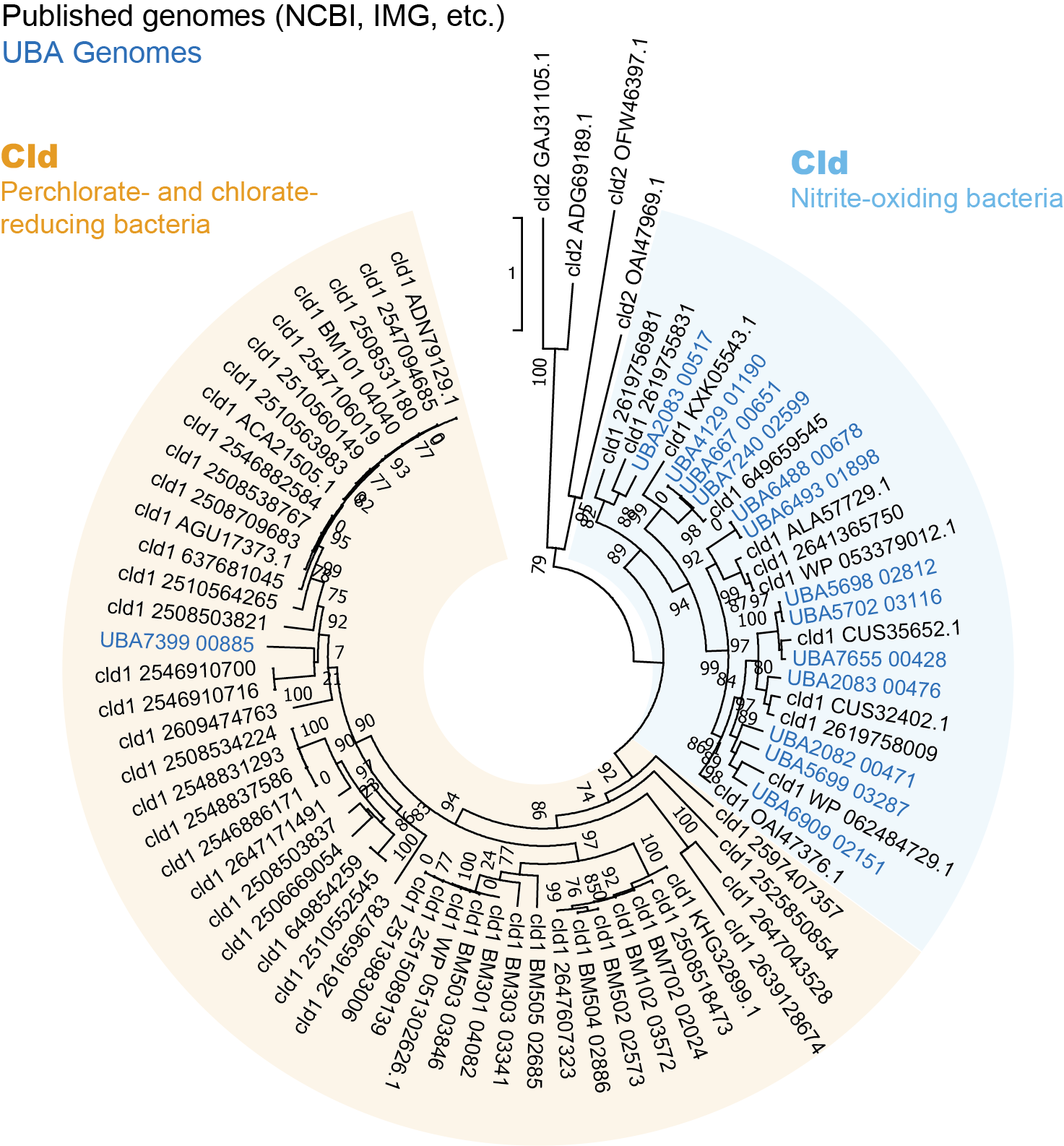

A helpful starting point could be comparing whether metabolism and/or habitat influences where an organism resides in “amino acid space.” For example, I noticed in plots of oxygen-influenced amino acids like cysteine vs. histidine, dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacteria clustered together (with high Cys content) and anoxygenic phototrophs clustered together (with aerobe-like Cys content). Then there are interesting exceptions, like the fact that cultured Campylobacterota, which are mostly microaerophilic, tended to look like anaerobes in cysteine content.

Evolutionary transitions

One exercise left to the reader was performing the in depth analysis of the phylogenetic distribution of growth conditions. How many times have different conditions evolved? How phylogenetically conserved are they? Are conditions even distributed across Archaea and Bacteria or do certain groups tend to have different conditions than others? An example of this work using extreme halophiles in Archaea just came out this week. There are lots of interesting questions left for you to tackle.

Finding genes related to physicochemical conditions

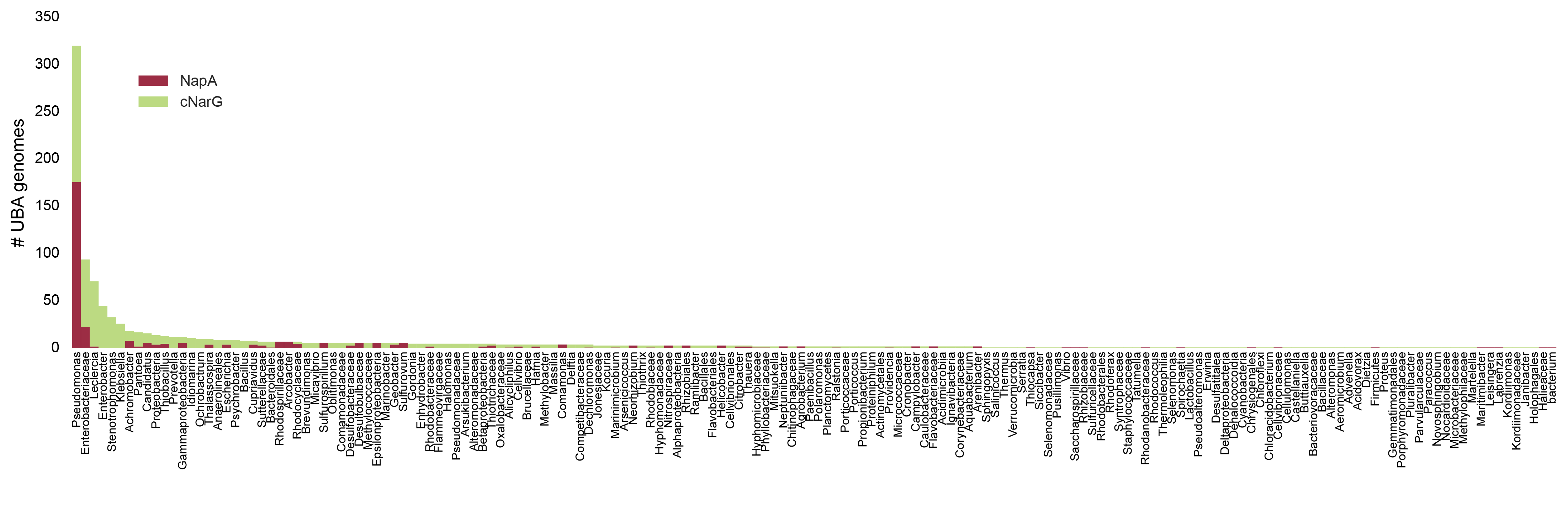

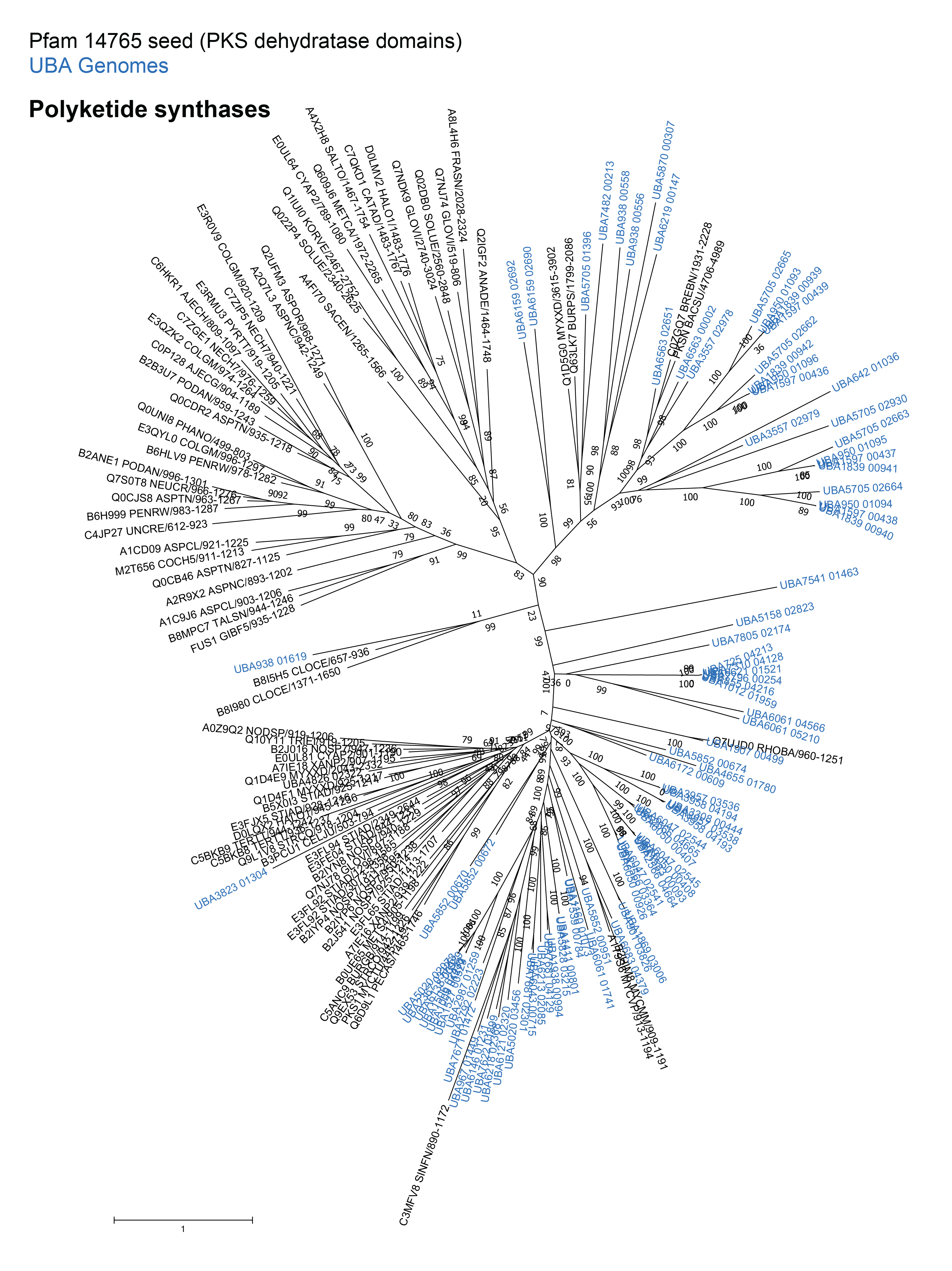

We chose to not build a gene-based model because we wanted to build something that would be accurate for new organisms. Before trying to predict a traits with genes, you should ask yourself: of all the genes in all microbes that influence this trait, what % are found in organisms in my training dataset? For a single deeply conserved pathway like denitrification, that representation might be very high, perhaps >99%. For a complex trait with many genes involved like living in a particular temperature/pH/salinity, we suspected it’s unlikely cultivated microorganisms could represent uncultivated microorganisms.

Ironically, the sequenced-based models we’ve provided might change that equation. Now you do have data on growth conditions for diverse microorganisms on which to build models. I recommend people try this, with a couple important suggestions:

- Select a subset of genes to be features. Models overfit when there are too many features relative to the training data. You should only feed in genes to a model that you have linked to conditions. This feature selection can be part of a model training pipeline, or it can be a separate investigatory process.

- When selecting genes, use held out taxonomic clades to test the selection. This is the most likely place where you will mess up and introduce data leakage: you find the genes most correlated to optimum pH across all genomes, then you use those genes to build and test a model with proper cross-validation and test sets. Where did you go wrong? When you selected correlated genes, you use all genomes, including those later in the test set, which means that your model had access to test set information. To truly know if your gene-based model is robust to phylogeny, you need to holdout test data from feature selection as well as later modeling steps. Ideally, feature selection is part of a model training pipeline.

- Account for missing or multicopy genes in metagenome-assembled genomes. I recommend emulating the modeling work described in the Davin et. al 2023, where they used a gradient boosted regression model trained on genomes with random gain or loss of genes. If you see in training you can’t accurately predict growth conditions on genomes with missing or multicopy genes, your model won’t work in practice on MAGs.

Your work could identify the genes that correlate with life at different temperatures, pH, and salinities, which could be helpful for biotechnology.

Wrap-up

The Cultivarium team hopes this tool provides a lot of value to researchers. I hope this blog post has provided you with a new interest in growth conditions and genomics and some ideas of what to research next. Feel free to reach out with any questions.